The Oscars are just around the corner. This year, the Academy has extended the Best Picture field from five to ten nominees, opening Oscars not only to long shot contenders, but also the very real possibility that the 2010 awards can change the landscape of film.

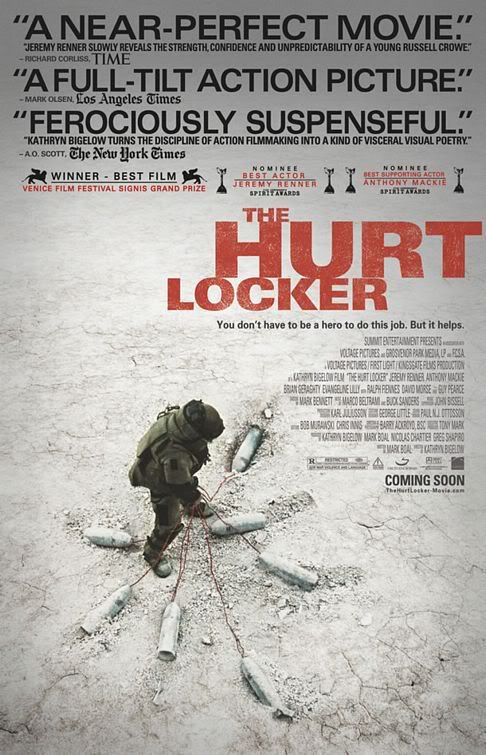

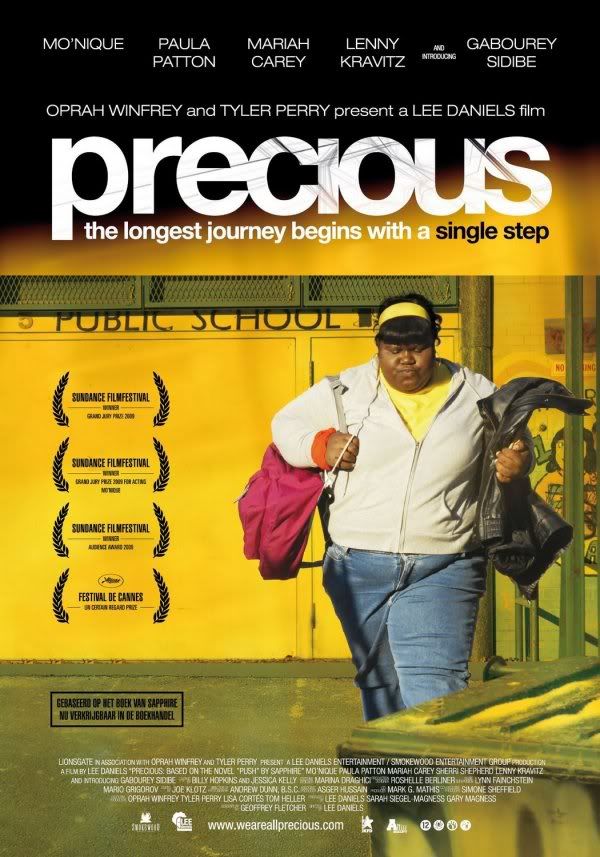

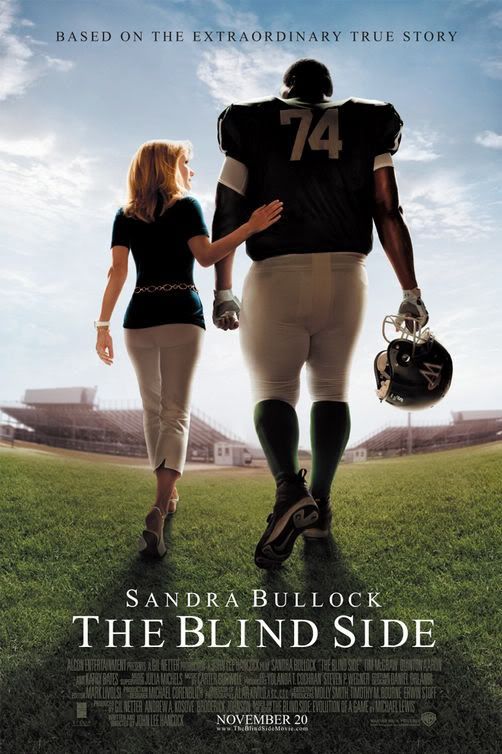

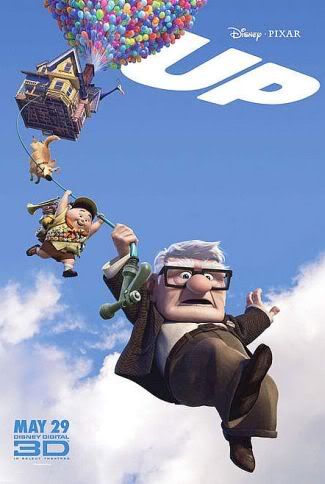

Let’s look at the nominees. The British Academy recently gave its high awards to The Hurt Locker, as did the Director’s and Producer’s Guilds of America. Avatar has made over $700,000,000 in the US alone. Precious has made history as being the first Best Picture nomination to be directed by an African American (in this case Lee Daniels). Why The Blind Side was nominated is anyone’s guess. I’m assuming it’s the same race and class guilt syndrome that won Crash Best Picture over Brokeback Mountain. Up in the Air is apparently fantastic, but an existential comedy doesn’t really stand much chance against the first great Iraq War film. An Education is there to appease the critics who fell head-over-heals for it, and A Serious Man is….well, they needed a tenth nominee. But really, if the whole hoo-hah of the Academy Awards has anything to do with intelligent, progressive filmmaking, the genuine competition would be between three of the films with the least chance of winning: Inglourious Basterds, UP, and District 9.

First things first and don’t get me wrong here: The Hurt Locker and Avatar are both fantastic films. The Hurt Locker is the first Iraq War film to give an honest, unpretentious view of the conflict, in a completely unpartisan way, focusing exclusively on the experiences of the soldiers. It’s tense and intelligent, with great performances and taught direction. But ultimately, it’s a war film, and while it’s a great war film, it’s something we’ve seen before.

Avatar, on the other hand, is like nothing we’ve seen before: giant blue aliens running about fighting with wild jungle moon creatures and men in various types of flying, walking, and driving machines. The technological advances James Cameron developed for the film open a world of limitless possibility. The technology allowed him to create a wholly original and completely imagined world. The plot of the film, on the other hand, from the jaded soldier finding peace with indigenous peoples to evil military and corporate personnel trying to muck things up, are staples not only of Hollywood past, but integral components of an endless parade of archetypal myth.

But though it can be perceived as (and has been criticized for) being largely generic, Avatar is the exact kind of film we need in the public consciousness. It is a movie that teaches us to think beyond our own confines, to believe in the potency of the spirits of the Earth, and to behave decently towards others. Through concrete example, it shows us why tolerance is important and that being a decent person is ultimately a worthwhile pursuit. Avatar is a great, even classic film, that children of countless generations (probably mostly boys, I’m guessing) will watch again and again on their TVs and computers the way I used to wear out my Star Wars VHS, but the reason for that is its adherence to tradition.

Ultimately, neither Avatar nor The Hurt Locker need an Oscar to attain classic status; they’ve already won that through their excellence. Rewarding either film would not only be unimaginative, it would redundant and pointless.

Precious is an interesting film. The ensemble works magic with its characters, and Lee Daniels’ direction brings an unpretentious realism to the film. What in less capable hands could have been very generic is a harrowing, intense drama. The film is also very important for its bravery. It is a film by African Americans, about the African American experience, which casts overweight and otherwise very normal looking actors (even Mariah Carey and Lenny Kravitz manage to look average), and puts them into realistic settings. There is nothing Hollywood about the look and feel of Precious.

Unfortunately, for the film, its plot errs to the familiar. There are too many inspirational classroom scenes, which are reminiscent of dozens of films, from Lean on Me to Dangerous Minds, and though Precious manages to avoid many of the painful trappings of similar films (white teachers educating the ignorant colored folk being the most heinous of these), it is, ultimately, something we’ve seen before. Thankfully, it also happens to be a hell of a lot better than nearly every other film in its class.

Let’s talk Quentin Tarantino, who has been a household name for over fifteen years. With Inglourious Basterds, he’s managed to do something near impossible for celebrities of his stature: subvert his image with his talent.

Tarantino virtually defined the cinema of the 1990’s. The graphic violence, profane dialogue, pop-culture references, self-consciously stylish gangster flicks, long tracking shots, and influence of the French New Wave – all of our 90’s film staples – can be attributed to Tarantino.

Yet post Jackie Brown, Tarantino began to parody himself. He made pictures that, though touched with his previous prodigious talent, were solely referential. They failed to push the envelope. Tarantino had failed to be Tarantino by becoming Tarantino.

With Inglourious Basterds, he’s back in top form. The World War II fantasia is original, bizarre, and unexpected. The film is broken into chapters, with a ludicrous Hitler parody, Brad Pitt scalping Nazis, SS film premiers, and a re-imagining of the war’s ending that’s as stupid as it is genius. With Basterds, Tarantino has proven that, though he hit the zeitgeist with Pulp Fiction, it wasn’t lucky; he is as talented, strange, and original as we have always expected.

Though Basterds doesn’t stand much of a chance, Tarantino has done something nearly impossible in Hollywood: he has reinvented a genre that’s been dead for ten years. While genre reminaginings come along every generation or so, from Se7en’s recapitulation of noir to 28 Days Later’s revelatory zombie apocalypse, Tarantino has taken one of the most rote, bloated genres of Hollywood history – the World War Two Film – and completely reinvented it. There are no concentration camps, no great battles, no real heroes. The morality of the characters is subjective: the violence of the Americans is no different from the violence of the Nazis (of course, leaving out any blatant Holocaust references makes this a lot easier); a group of young German soldiers are some of the most sympathetic characters in the film. The futility of violence met with violence is strongly reiterated (except of course for the gleefully ultra violent ending). Nearly everyone involved directly in the war is either sadistic, or weighing their chances in a menagerie of violence beyond their control. The only truly defensible characters in the film are a Jewish theater owner and her black lover: the victims of prejudice and discrimination. Yet Tarantino wraps all of these things in ridiculous comedy and prodigious dialogue, so that much of the social value of the film is between the lines.

The critical reaction to Tarantino’s film, though largely positive, shows a very disturbing lack of imagination on the part of some self-important critics. Manohla Dargis, of the New York Times, condemned one character’s comparison of Jews to rats (“The invocation of Jews as rats is ghastly” – NY Times, 8/21/09). But the character doing to comparing is a Nazi, who as we know didn’t think terribly fondly of the Jewish population. Ms. Dargis also criticizes the film for having such a charming fellow (Oscar nominated Christoph Waltz) play the lead Nazi. Correct me if I’m wrong, but Hitler himself was an incredibly charismatic leader. This charisma played a large part in the Nazi propaganda machine. If Tarantino’s film were melodramatic Oscar-bait like Saving Private Ryan or Schindler’s List, I doubt anyone would bat an eyelid. But because Tarantino can be both facetious and insightful at the same time, he confounds most journalists, and will probably turn the Academy off to his film.

On to floating houses. UP is Pixar’s latest creation, and though it’s not quite as good as animation high water mark Wall-E, it is a phenomenal work none-the-less. Now, of course, UP will be thrown the Best Animated Feature bone and all will be well in the world. But UP is much more than that.

Pixar has been working vigorously, and against many cultural biases, to realize animation’s full potential. Mostly we look at animation as a medium for kid’s movies, cutesy stuff with talking animals and the like. But really animation is film’s greatest liberator, the visual equivalent of the novel. Anything that can be thought can be done. Gleefully subverting type, Pixar creates characters as sympathetic as any human actor, and emotionally potent stories of joy, despair, loss, and redemption. The initial sequence, of principal couple Carl and Ellie growing old together, is heartbreaking, and would have been completely ham-fisted and unbelievable if it hadn’t been rendered in animation. The sweetness and sorrow of the scene braid perfectly in director Pete Docter’s parallel world.

Though the elements of UP are familiar – it’s got the talking dogs, the curmudgeon, the lonely kid – the film puts a distinct spin on everything. First, the setting of the Venezuelan tepuis is gorgeous and ethereal. A flying house lifted by thousands of balloons is a brilliant hook, but doesn’t dominate the film. The talking dogs can only talk because they have collars that allow them to. At the end of the day, UP is a brilliant and heartfelt film that is familiar enough to draw us in but new enough to wow us, and is something for everyone, which is one of cinema’s great promises. Though it doesn’t stand a snowball’s chance in hell of winning, it perfectly illustrates Pixar’s ability to think outside the box: they make films using animation, not animations that are films.

And last but certainly not least, those pesky South Africans. District 9 is brilliant in so many ways it’s gonna take a minute here to break them down. Let’s start off with what’s most mentioned: the allegory. An alien ship stalls over Johannesburg, and its inhabitants, known colloquially as Prawns (and they do look a great deal like shrimp) end up in a refugee camp. So what we’re talking here is commentary on racial situations of times past, and the sordid history of South Africa?

Well, yes. But part of the genius of District 9 is that, while it can very easily be read as commentary on apartheid, the notion is abstracted, and as such can be applied to any struggle, past, present, or future. In a demented way, District 9 is the most educational, moralistic, and important film of the year because it uses a phenomenally entertaining yarn to show us the absurdity of our own prejudices. Despite this, the movie steers clear of the didactic.

As with Inglourious Basterds, District 9 completely redefines an established genre, and as such is, like Basterds, unlike anything we’ve ever seen. It puts aliens in the real world, as the victims of humanity. While most films that have beings from outer space use the aggression of aliens as an excuse to unify humanity, District 9 paints a much more realistic portrait of reactionary, insecure human cruelty, one which is born of fear and ignorance. By taking the action away from world centers like Washington DC or London and putting it in a former colony, the film shows us the world the way most of its citizens see it, rather than the glorified, anti-racist pap of The Blindside.

District 9’s final stroke of genius is in the class structure of alien society. The leadership aboard their craft has died, and the Prawns who become trapped on Earth are the working classes. They are not the brilliant scientist aliens who create brain probes and seek out leadership in an effort to destroy or bargain with them; rather, they are the tired, hungry masses. They are huddled, terrified, and very alone. The literal aliens are also figurative aliens the world over, refugees cast aside as victims of circumstance, who dream of nothing more than a homeland.

Director Neil Blomkamp, only 29 years old when he made the film, tells an entertaining, quickly paced action tale in District 9. He has stated many times in interviews that his aim was to draw the audience to the story, and let the rest of the film’s elements work their magic subtly. Unlike many Hollywood movies, which choose to hammer us repeatedly over the head with their message, District 9 wants to have a hell of a good time, and if we have the chance to notice the film’s allegories, or bold new definition of the sci-fi, alien picture, well, that’s just fine too.

UP and District 9 are the year’s best films because they give us hope, not just in the human condition (we all know that there are more than enough films in the world which do this, or at least try), but in the future of mainstream films. Pixar’s latest heartfelt fairytale, coming on the heals of the seminal Ratatouille and Wall-E, shows that the studio will continue to push boundaries of animation and challenge cultural biases that it is solely a medium for childish films. District 9 belongs to a new school of cinema, begun with a bang by Alfonso Cuarón’s unparalleled Children of Men, and is the most promising addition to the genre since Cuarón’s original appeared in 2006. These are films that create allegorical, distopian societies, which are deeply rooted in our day-to-day reality. They do not present fascistic states or sci-fi futurescapes, but give us a distorted version our own world, with its bureaucratic and capitalist structures pushed to the point at which they become impassable labyrinths. The enemies of these films are not the other humans, with malice in their hearts, but the creations of all human beings, the systems and ideas we prescribe to grown beyond our control so that they control us.

Now, all of this said and done, and where does it leave us? It’s easy to be cynical and dismissive about the Academy Awards, to label them a popularity contest and irrelevant to important, intelligent film. In a lot of ways, this is true, but the Academy has the opportunity to make not just its audience, but also studios and filmmakers think seriously about what makes a great film. If The Hurt Locker wins the top prize, which it probably will, a rash of Iraq War films will be green lit (admittedly, I look forward to Paul Greengrass’s The Green Zone with great anticipation). But, more likely than not, we’d get those films anyway. If Avatar wins, we’d get more fantasy films in space, most of which would probably be crap. In 1977, Star Wars basically insured the future of all sci-fi filmmakers, so we don’t really need Avatar to win. If Precious wins, it probably won’t be any easier for visionary African Americans to make films, and we’d most likely be deluged with message-based anti-racism films directed by well meaning wealthy, sheltered people. Yikes.

Nominations for film such as Basterds, UP, and District 9 are surprising and essential. Certainly it will be easier for forward-thinking film to gain its due time in the spotlight with the field doubled. One of our great living indie filmmakers, Danny Boyle, helped a good deal with this when he and his latest, Slumdog Millionaire, took home top prizes in 2009.

A win for Inglourious Basterds would have no repercussions, because Tarantino is such a singular figure that it would be either his token Oscar or an anomaly of some kind.

But. What if UP wins? We can only hope that a win for UP in the Best Picture category would help validate animation as an art form, and also encourage more animators and animation studios to think outside the box. Or, maybe encourage a greater influx of progressive global animation into the cultural mainstream. And if District 9 wins? The studios may look to young filmmakers with original visions and nurture them, thus allowing the future of film to come to fruition, rather than marginalizing it to specialty divisions and eventually absorbing its stylistic tendencies, while leaving the substance to “art” films.

By rewarding UP or District 9, Hollywood will create a unique possibility, that to create new markets (it is all about business, after all), which in turn could lead to a more insightful, provocative pop culture, not unlike that of the late 60’s/early 70’s and early-to-mid 90’s. The relative success of 9 and Basterds, and the huge take of UP, show that the public is indeed ready for something new, and much more intelligent, than what we’ve been having. With the right decisions, the Academy could influence big business, which could have a profound and profoundly positive affect on our global mainstream culture. With directors like Guillermo del Toro and Paul Thomas Anderson working with major studio approval (and even, in del Toro’s case, a huge budget), the bomb is in place, the fuse just need be lit for a mainstream progressive film explosion.

So really it’s just the Oscars, and really it’ll be the same old films again. But by expanding their nominees for Best Picture from five to ten, the Academy has given us a glimmer of hope.

2 comments:

District 9 should win.. Mocumentary + Prawns

The Hurt Locker is awful and Avatar is the worst movie I've seen all year and I've seen some horrible stuff. The academy should be punished if they award visual effects over plot line.

Post a Comment