A recent tour of Chapultepec Castle revealed some serious bullshit re: Mexican history and pre-Hispanic culture.

A recent tour of Chapultepec Castle revealed some serious bullshit re: Mexican history and pre-Hispanic culture.

One of the first things our group learned on the exhaustive tour was that, well, despite what everyone might think, actually Spain didn’t conquer Mexico because at the time there was no Spain per se, and certainly not a unified notion of Mexico as a nation, so really all that you had was people fighting people.

While some might take this an effort to work some genuine historical analysis into an otherwise very literal relation of “Mexico’s” post-“Spanish” domination history, in the context of the rest of the tour, it reeked of the feces of a certain bovine animal. Bullshit alarm #1 goes off.

Let’s think about this. There was no Spain, as it were, as the country it is today. Granted, that’s the way it was. And of course there was no Mexico as the unified country known today as Mexico. But there were Spanish peoples, who came to what is now Mexico and perpetrated severe atrocities on people who are the ancestors of who are now Mexicans, thus they too are the Mexican people, if not in name then in blood and culture.

And so by saying that there was no Spain and there was no Mexico puts the idea in the mind of the visitor that it was just groups of people vying for supremacy, and that the European colonial power isn’t precisely to blame. It’s possible that this is done for PC reasons, to avoid offending Spanish visitors and invoking the ire of Mexicans (ire being directed toward the Spanish).

Reasons regardless, this attempt to deflect attention from things like rape and slaughter and slavery, and toward this relatively pointless minutiae about the development of kingdoms and modern-nation states gives a very suspiciously skewed perspective of what was actually going on at the time.

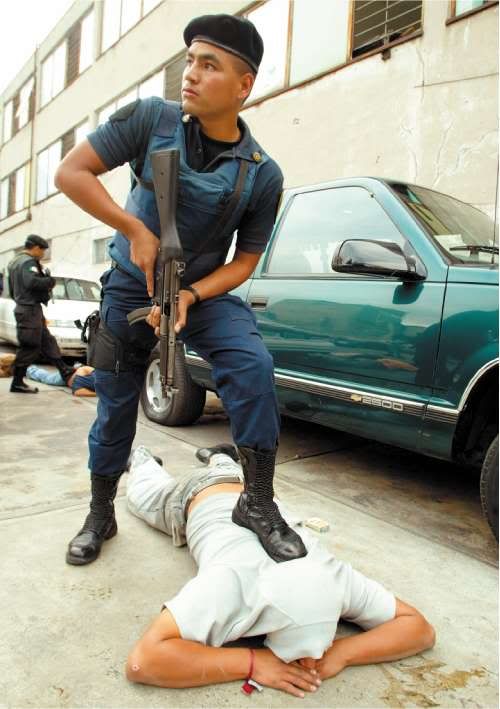

The tour continues, some rather pleasant images and historical nuances are departed upon us, and we come to a display of human skulls with giant holes driven through them. Thus begins the inevitable section in which we deal with violence, warfare, human sacrifice, whatever else you may have had back in the day that puts the weak stomach ill at ease.

Our tour guide tells that pre-Spanish Mexico was far from the wanton bloodshed of a certain Mel Gibson film. In fact (we’re told), human sacrifice didn’t happen that often and was done for a reason. We’re told, think of it like this:

It’s Christmas time and some aliens come down to earth and you invite them in for tea and you’re having this nice snack with these extraterrestrials, discussing a certain episode of M*A*S*H that had been beamed into space, when they see the dead tree in your house. Hold the phone.

The alien leaps to his/her/combination thereof feet. “Dear god! Why have you got a dead tree in your house?! This is a phenomenally grotesque display of arboreal sacrifice!”

And then it’s your job as the host to be like “Well, actually, it’s this annual ritual that we have, where we cut down trees and bring them into our houses and decorate them. It’s actually quite nice.”

“Oh. I see. Well then, forgive my impertinence.”

And thus was explained the human sacrifice of indigenous Mexican cultures: Dismembering and beheading captives, stripping their skulls of flesh, and impaling them in garish rows on fences as a totalitarian scare tactic is essentially the same thing as cutting down a tree and putting some lights on it and having a little gift giving ceremony.

Or, rather, comparing human sacrifice to Christmas trees is a way to imply a certain innocuous quality in the sacrifices, so that pre-Hispanic cultures are not seen as barbaric. Being relatively intelligent, we of course see that what’s going on here is that the castle and its emissaries are attempting to create a cohesive vision of Mexican culture and history for the visiting foreign legions of tourists so that said tourists will go home thinking Wow, Mexico has such a fascinating and rich cultural history and not Man that’s fucked up that they cut people’s heads off and impaled them on sticks.

And yet to assume that guests to this magnificent country are unintelligent enough to be unable to accept a country that is not as multifaceted and contradictory as Mexico is quite frankly insulting. Certainly, there’s no harm in seeing the human sacrifice from the sacrificer’s point of view, and it’s an interesting tidbit about the countries not actually existing per se, but to try to alleviate responsibility for what could be seen as barbaric in an attempt to placate tourists is a dangerous revisionist tactic.

We can only hope that this will be rectified in the future.

Thoughts on Things - Bullshit