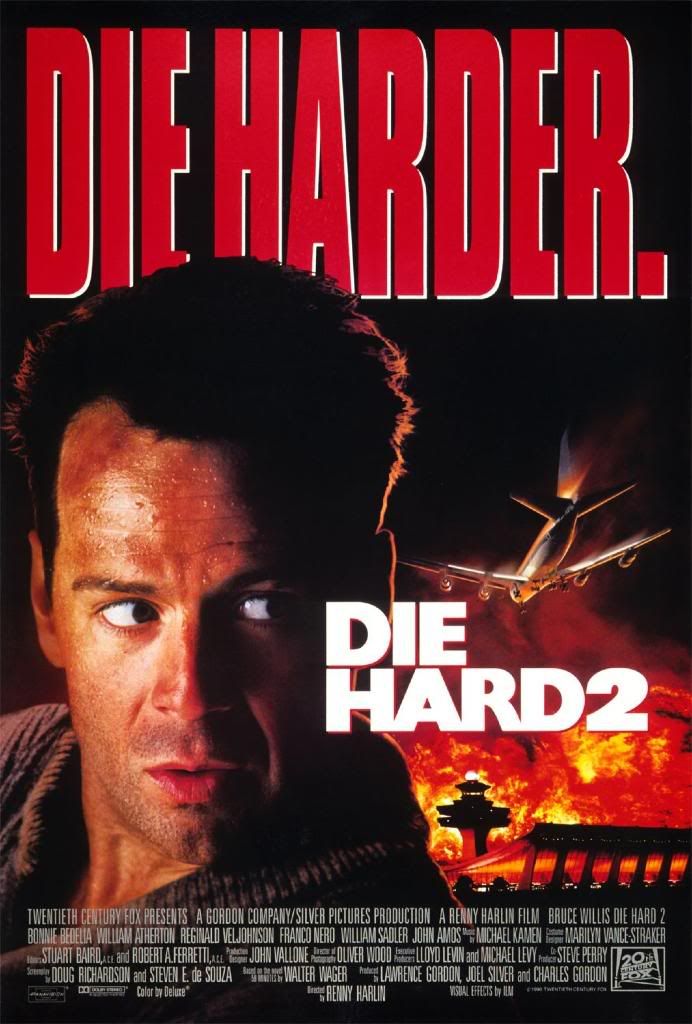

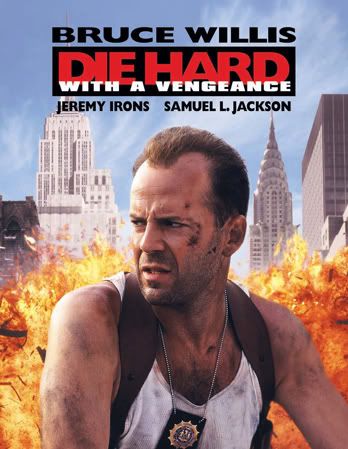

Watching Die Harder (Die Hard 2) and Die Hard: With A Vengeance (that’s DH3 for the uninitiated) back to back, its easy to see the many differences between 80’s and 90’s mainstream cinema, and the way those differences reflect shifting cultural trends at large (endnote 1).

The Hero

The first film deals in absolutes: John McClain is a hero. The villains are evil. The captain of Dulles police is a jackass and a bureaucrat, placed firmly in opposition to McClain, who’s a go-getter, an every man, the guy who knows best. He is a proactive American who does the right thing, much like an upstanding white man would as per the Bush (first Bush in this case) administration’s representation of America.

McClain is introduced to us in the film’s first shot, rushing out into snow and traffic, a man on a mission. That mission: stop his car from being towed. This shot introduces the setting, the time of year, and McClain’s restless, aggressive personality. These things remain staples of the film as it progresses, all of the action taking place between two locations; the airport, and a church, which is set up by the second scene. This is clean, precise, mainstream filmmaking.

Having a coffee in one of the airport’s cafés, McClain notices some very suspicious men decked out in portentously dark coats with very slickly jelled hair passing suspect packages to one another beneath at table. Though off-duty, he takes note none-the-less. McClain approaches two airport cops. As it turns out, one of them is the fellow that had his car towed just ten minutes earlier. John the knows he can’t trust these guys to believe him, because he knows they are uniformed bureaucrats; the men won’t investigate his claim to nefarious activity because he rubbed them the wrong way earlier. They are the inept authorities, and he is the man with a plan. The cowboy. McClain ends up following the suspected n’er-do-weller, and thus begins the action – incited by McClain and his instinct. In DH2, the hero creates the story.

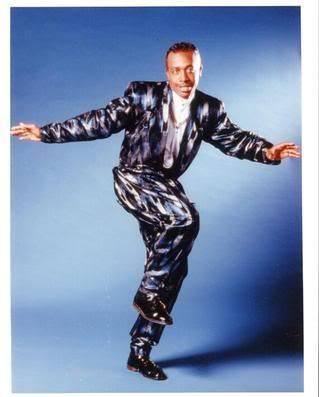

(A) DH2's heroic McClain, poised (B) The massive 80's movie star (C) A svelte Keanu Reeves in Speed (D) Exhausted, alcoholic McClain, not really ready for action

DH3 introduces us to a very different John McClain and a much more ambiguous world. He is absent the first few minutes of the film, which give us introductory shots of New York. Real locations are introduced, in opposition to DH2, which, though taking place in DC, never gives us anything beyond sets, apart from a few establishing shots. The camera panning along the Upper West Side, a building explodes, sending cars and people flying into the street amidst the debris.

We cut to the inside of a police station, and the captain, who, unlike the snippy, uniform wearing, mustachioed prick of the first film is a tired, weary guy in a suit overwhelmed by the gravity of the situation. By and large what we find of the police in this film is that they are sarcastic guys (and their female secretaries – some things never change) in disheveled, cheap suits who just want to do the right thing (endnote 2) , evocative of the noir heroes of yesteryear.

The bossman receives a phone call from the villain who, speaking in riddles, demands John McClain. The captain informs him McClain is on suspension. Already our hero is a man with some demons. The villain retorts that he doesn’t care where McClain is, it’s him he wants, and no one else.

Our first shot of McClain points downward, diminishing our previous, heroic notions of him. He’s sprawled on the floor of a van, dirty, hung over, and barely with us. His wife’s left him. He’s a directionless drunk on the verge of being tossed off the force. McClain is very clearly an anti-hero, much more Bogart to DH2’s Clark Gable-styled hero. He doesn’t burst into the action or incite the plot; he’s off drunk somewhere while the world is falling to shit and is reluctantly called into battle. The film’s plot unfolds accordingly, the villain sending McClain here and there as he pleases, until McClain finally souses his number and changes the rules.

To extrapolate this, we need look no further than the Soviet influence on the American perception of the world. While we had the Soviet’s, we had a duality, a binary relationship in which there was an “us” and a “them”, with the world’s various states pretty much split accordingly. This duality directly informed DH2. As the wall came down, so did the duality; the world very quickly became a plurality, most of its compositional elements being undeveloped nations ravaged by the shady dealings of the cold war, shaking their fists for justice.

During the Regan administration, Iran-Contra, the fighting in Afghanistan, the intermittent violence between Israel & Palestine and Somalia & Ethiopia were all just repercussions of the big fight: America vs. the Evil Empire. The Clinton administration, however, faced real, sectarian violence that had nothing to do with America and its battles directly, though was of course a repercussion of colonialism and the cold war era – Rwanda, Serbia & Croatia, Mogadishu – all of it a direct cause of American or European intervention, weapons manufacturing, and the unfortunate practice of grouping peoples with great enmity toward one another into singular nation-states. As the media grabbed onto these conflicts to highlight a world of intense brutality that had been hidden behind the Soviet veil, American awakened to reality of the global situation, much like John McClain is pulled into a situation of terrorism far beyond his control in DH3.

The Villain

What’s a film without a bad guy? And yet what different bad guys they are. In the first picture, there are two villains, one working with a crew of military mercenaries to free the other, who is a despotic general being ferried to the US to be held accountable for his crimes. This generalissimo looks a good deal like Fidel Castro, smokes cigars, and smiles pleasantly as he strangles and shoots his captors. He is introduced via a news bulletin shown on a television in the airport.

The man in charge of the team working to free him is introduced nude, doing tai chi in his hotel room. He is muscular, angular, and a mean-looking motherfucker. He dons his clothes and joins his party, all of whom are dour and similarly angular (endnote 3).

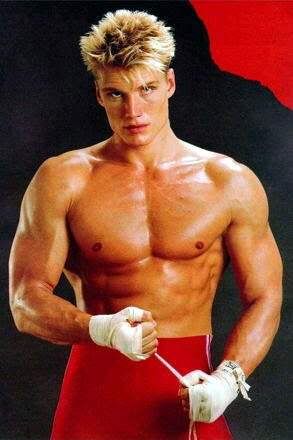

The motives and aesthetics of the villains in DH2 are very much of a different era. Their look is very simply fascist: they wear military boots, long coats, and tucked-in button ups, mostly in shades of black and gray. They are terse, remorseless, humorless, and all, save the lone black man (whom I guess at this point we can call token), have slicked-back hair (the black fellow sporting a fashionable flat top).

The men are, like McClain, absolutes. They are bad. Rather than their character stemming from their motives, their motives stem from their characters. These men are the baddies, and that’s why they’re doing bad things. They crash loaded civilian planes into the tarmac, smiling wryly, killing hundreds of people, to make a point. They saunter around with automatic weapons blowing people away, because they’re bad and they don’t care. They are archetypal 80’s nemeses, fitting nicely in the mold carved from Dolph Lundgren’s evil Soviet in Rocky down to the badass invisible alien in Predator. What theses villains want is simple, and, apart from third act twist that wasn’t too hard to see coming, so it the plot. From the get-go, we know pretty much what’s going on, who’s going to stop it, and how. The pleasure comes from watching it all unfold.

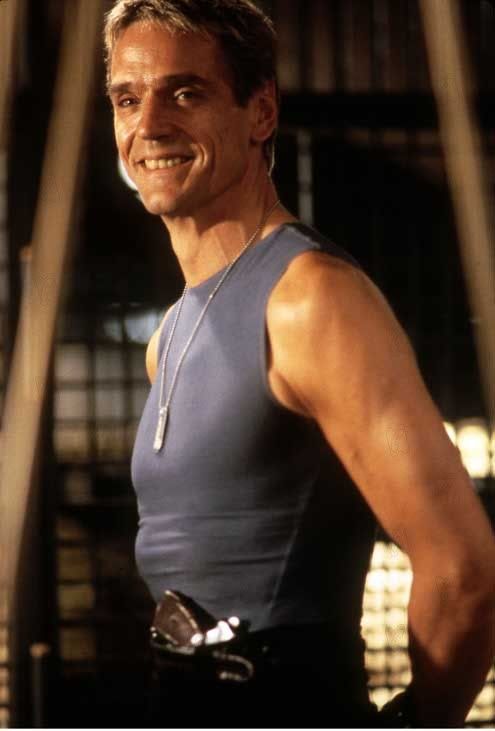

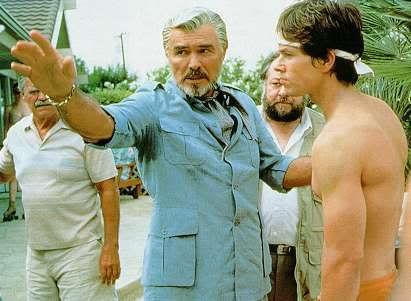

(A) Proud Soviet Dolph Lundgren, kicking ass in the mid 80's (B) DH2's villain, naked and well muscled (C) Kevin Spacey's cerebral Se7en villain John Doe (D) Ironic intellectual Jeremy Irons in DH3

The villain of DH3 is a very different man. We don’t even see him until about 20 minutes into the film. He comes to us primarily on the phone, presenting himself as enigmatic and intellectual, throwing out riddles and games for the weary police to scratch their heads over. The police bring in a psychologist to look at his motives. This is a very 90’s trend; we can look to Silence of the Lambs, released in ’91, as the harbinger of the “motives” game played in 90’s cinema (endnote 4). The psychologist called in to understand the motives of a criminal and use this to track him down. Like Denis Hopper’s absent criminal mastermind in Speed and Kevin Spacey’s phoned-in malevolence of Se7en (endnote 5), Irons’ character is a sort of omniscient cat playing games with the good guy mice. Indeed, the entire concept of explaining the motives and a villain is very 90’s, and very post-communist, as in aforementioned world of pluralities, one can never be quite sure why anybody is doing anything, without looking to extensive psychoanalysis or extenuating historical circumstance.

This trend of understanding the psychology of character and person, and the way it dictates personality and motive, extends throughout 90’s cultures. To paraphrase Billy Corgan: our generation was the first to publicly tackle child abuse. Herein we will attempt to neither assert nor deny that, but it makes a very interesting point: one of the dominating trends of 90’s pop-culture was the explanation, the uncovering, the “digging deep”. Nirvana brought drug-abuse and the disturbing effects of the broken home to light. Eddie Vedder and Pearl Jam spoke openly of childhood trauma and abortion. Irvine Welsh exposed the exploitation and desperate violence of the working class Scottish situation, and the way in which the bleakness of that reality was a direct conduit to drug abuse, alcoholism, and the perpetuation of working class violence. The list could easily go on; suffice to say, this was a driving force in the culture of the 90’s, and its presence in DH3 highlights perfectly the break in the previous trend of looking at the world as black and white (again, a duality, as with the Soviet/US duality, because, as we’ll see, the world of DH2 is predominantly white). The post-Soviet-world point is doubly reinforced by the DH3’s villain, who happens to be a former East German intelligence expert, and is now a man adrift in plural world (endnote 6).

Jeremy Irons is a flippant, ironic, intellectual villain in DH3. He speaks in riddle, has frosted hair, and isn’t in the least physically imposing. Rather, he dominates with his intellect. Here we see the rise, in the 1990s, of the haughty power-of-intellect movement. As undergraduate degrees became much less valuable currency, and the coffee shop culture began to take hold, we saw in the US 90’s what we saw in France in the 30’s: a bunch of fancy-pants intellectuals sitting around in bay-windowed cafes trying to outsmart each other, pursuing higher degrees and spouting irrelevant minutia in effort to obscure insecurities and the need for acceptance (endnote 7). Tarantino, the great filmic even of the 90’s, was an obnoxious know-it-all. Kurt Cobain was sardonic and guarded, displaying a hidden but intense intelligence. David Foster Wallace wrote an 1100-page tome about what it means to be American, full of footnotes, tangential historical asides, vernacular Canadian French, and reams of anally precise grammar (endnote 8) . Where as the baddies in DH2 shoot, stab, and explode airplanes, the nefarious intellectuals of DH3 play games with their nemeses, and out smart them.

Race, Religion, and Body Image

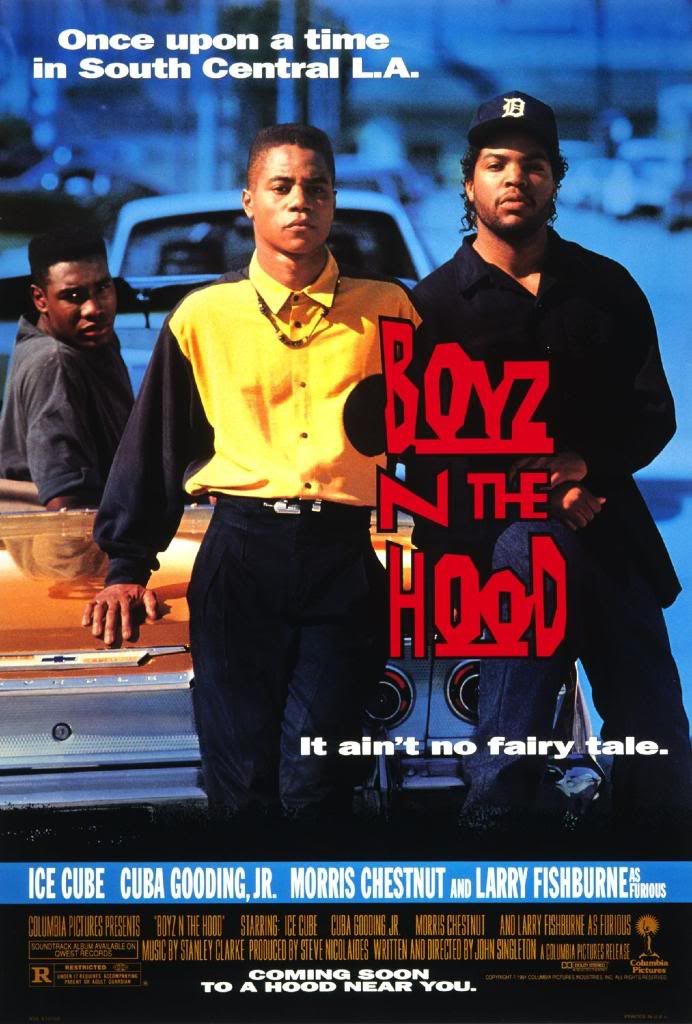

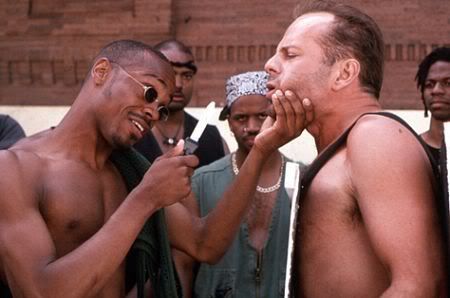

DH3 is very glaringly a product of the post-L.A. riots cinematic, and more broadly cultural, race dialogue that exploded into the American consciousness in the infant years of the 1990’s. Spike Lee’s Do The Right Thing led the charge, coming a few years before the issue stepped onto a much larger, nationally accepted stage of criticism. DH3 is populated with a multiracial tableau, from the black police secretary to the Native American detective, and the very realistic NYC school scene filled with children of all the world’s races. Samuel L. Jackson’s character, introduced through a quick monologue that sounds like Lawrence Fishbourne’s entire Boyz N the Hood creation, Furious Styles, crammed into thirty seconds' worth of dialogue (endnote 9), becomes the mouthpiece of racial tensions throughout the film.

The movie’s first proper set piece throws us right into the racial melee. The villain demands that Bruce Willis walk around Harlem wearing a sign reading “I Hate Niggers”, or another bomb goes off. John McClain dons a sandwich board with said message and begins traipsing around north of 125th Street. Suffice to say, this is where he runs into Samuel L. Jackson’s character. This is also where we as the audience begin to see the painful flaws of the film’s “let’s tackle racism” stance. That Mr. Willis’ character dons a sandwich board reading “I Hate Niggers” says less about the film’s desire to take on very serious and deep-seeded racial problems facing contemporary America than it does about their desire to attract attention with a grossly crass and exploitative gimmick; the flippant, ironic, supposedly post-racist use of the n-word by white characters and white filmmakers in the post-Pulp Fiction world of cinema is a very sad trend, and one that DH3, despite its well-intentioned liberalisms, revels in.

As McClain strolls, a group of young black men passing around a basketball (endnote 10), drinking beer from paper bags, chill out on a stoop. Mr. Jackson’s character runs over to John McClain, divines that he is a cop, and recommends he get the fuck outta dodge right quick, or else said group of fellows would attack and possibly kill him. Right on cue, the group walks over, shouting insults, brandishing weapons, and eventually assaulting McClain. While the scene is heavily influenced by the black hoodlumisms of Boyz in the Hood, it very disturbingly lacks that film’s multifacicty. Where as Boyz presents both gun-tooting, 40-swilling thugs who perpetuate the ghetto’s violence and intelligent, straight-laced, academic standouts who are unfortunate victims of circumstance, DH3 seems to think that any group of young black men hanging out on a stoop is going to kill somebody for wearing the n-word (endnote 11) on a sandwich board. What we see here is something very prevalent in 90’s culture at large; a PC attempt to take on serious issues plaguing society that ends up falling victim to it’s own intentions.

Though Mr. Jackson’s character does make a few very good points – the moment when he tells McClain he doesn’t give shit about him as a person, that he saved him because the last things Harlem needs is a murdered white detective, is powerful and poignant, thanks in no small part again to Jackson’s ability to dredge dignity out of basically anything – it becomes the film’s running joke that McClain assumes Jackson can perform various tasks (pick a lock, run quickly, hot-wire a car, shoot a gun, etc) because he’s black. As it turns, he can do all of these things, and very well, apart from the gun shooting. So, despite the filmmaker’s attempt to tackle a very 90’s issue (look to American History X, Dangerous Minds, Law & Order, and any number of anti-racist 90’s punk songs – notably H20’s cover of the Dead Kennedy’s “Nazi Punks Fuck Off” (endnote 12) – for proof that white Americans were obsessed with dealing with race in the 90’s), the movie ends up being more racist than not, enforcing stereotypes rather than fighting them.

(A) Typical 80's view of an African American (B) Dennis Franz's chubby police captain (C) Racial demographic sea change via Boyz n the Hood (D) Evil black men with sculpted bodies waiting for white people to cut in DH3

For DH2, race is a non-issue. The color of the character’s skin is never mentioned. Despite the very different, more-naturalistic approach to race, the film is much less realistic in the racial demographics it presents.

DH2 takes place in Washington DC, a city with a large African American population. Nearly every bystander is the airport is white. Nearly every airport employee is white. Most of the cops are white. In fact, nearly everyone in the film is white. Let’s list the non-white characters we noticed: Three black police officers, one black air traffic controller (a sympathetic, central character), one black villain, who we think was John Leguazamo in a very brief cameo, a black baggage handler, a few black guys pushing luggage carts, a Latin American generalissimo who could very well have been a white guy with an affected accent and some make up, and a black army major. Everyone else, white. That’s about eleven non-white people. In the whole film. Give or take some extras, it’s not a very realistic representation of the country. So, while DH2 avoids some of the more painfully racist moments of its successor, it also presents a very skewed view of who Americans are and what they look like (endnote 12) . Not to mention that every black man in the film is either working for the man (moping the floor, pushing a cart, throwing luggage), or is walking around with a gun being very stern and stereotypically angry (note: not righteous indignation, simply misdirected hostility).

On the other side of this, DH2 is not afraid of portly characters. The airport’s police captain is balding and rocking a serious gut. Ditto with some of the airport’s patrolmen. The older male members of the airport staff have let themselves go a bit. DH3, on the other hand, seems very much afraid of any character who wouldn’t be set to run a few miles at a moment’s notice. This highlights a very interesting point: while the filmmakers of the 80’s racially misrepresent America, they present America’s body image in a relatively realistic way. The 90’s filmmakers, on the other hand, give us a racial panoply, but seem to think that everyone in the United States goes to the gym every day. This marks a shift in what the American audience was looking for (or at least, what film producers thought the American audience was looking for): in the 80’s, overweight characters present a realistic view of average America. In the 90’s, multiracial characters assumed that mantle.

DH2 takes place in a very Christian world. It’s December 24th. Characters make constant reference to the holidays. The airport is bedecked with more than one Christmas tree. The villains elect to hide out in a church. In the filmmaker’s presentation of the US, we are a Christian nation. DH3, on the other hand, is a very secular film. It’s action takes place in the religious neutrality of August. The only mention of religion comes flippantly, when Samuel L Jackson asks Bruce Willis how Irish people do the cross (endnote 14) thing. Again we see the very particularly 90’s, PC, Clinton-era interest in avoiding any specific mention of a ritual or categorization that might exclude any particular group of make a person or persons fell uncomfortable; the separation of church and entertainment is powerfully evident (endnote 15) .

The Influence of the 90’s Auteur

Unlike the 80’s, 90’s cinema was very much an age of the auteur. Trends harkened back to the 70’s, when rather than a system of studios pumping out product, a group of young maverick artists was forging culture and “cinema” (endnote 16) . Quentin Tarantino, Paul Thomas Anderson, David O. Russell, Gus Van Sant, and countless others brought a personal and much more artistic touch to cinema (endnote 17) . The influence of these independent titans reverberated through out the mainstream, and is certainly evidenced by DH3.

First, the camera work. Where as the second DH film relies mostly on static shots, fluid editing, and grand action set pieces told from omniscience, the third film seems much more interested in pursuing its characters closely, through long, Scorsese-esque tracking shots and hand-held camera work. The characters of DH3 are followed very closely and at ground level. From the taxi chase through Central Park to the somewhat ridiculous shoot-em-up in Montreal at the film’s end, the cameras are low, jumpy, and shot continuously. This reflects an interest in relating directly to characters, the post-modern belief that the character, not the plot, drives the story. The cameras of DH2 tell us that the plot and circumstances are of paramount importance; the characters are pieces to be manipulated within that system for maximum effect (endnote 18) . This style of camera work can be traced from Godard’s Breathless to Scorsese’s Raging Bull to Tarantino’s Reservoir Dogs (though the crowning achievement of 90’s tracking shots is the opening of Boogie Nights) and directly into the mainstream (endnote 19).

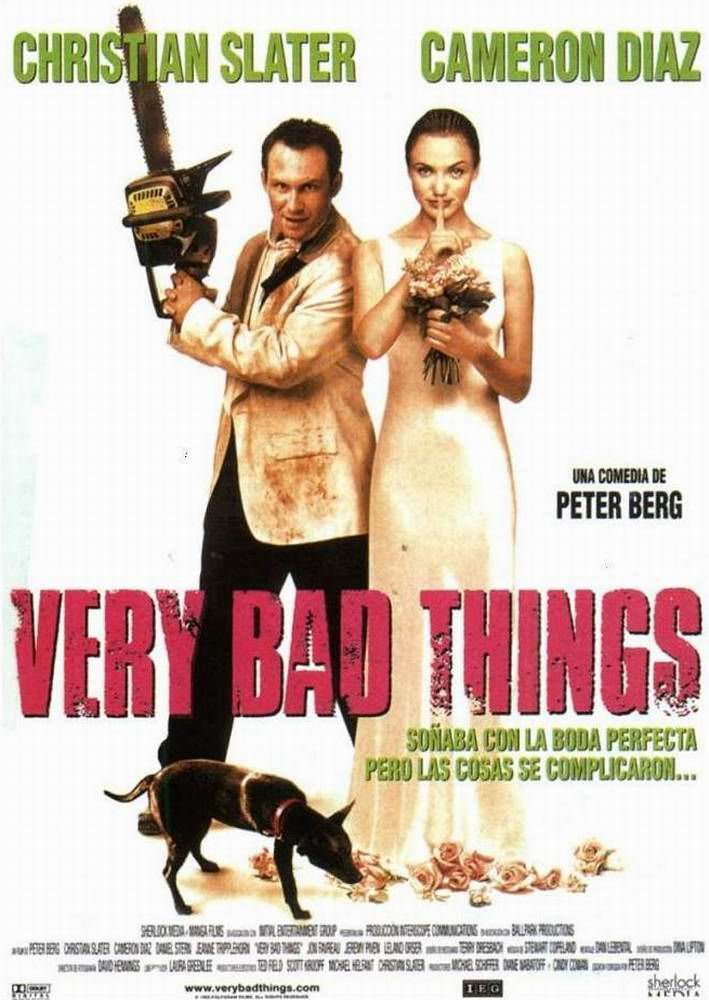

Film like Paul Thomas Anderson's Boogie Nights (A) and Tarantino's Pulp Fiction (B) influenced violent realism in the the mainstream such as (C) DH3 and studio-produced black comedies like (D) Very Bad Things

The ironic, post-modern use of music is another staple of 90’s cinema. In the film’s of the 80’s, we have mostly bombastic scores, with pop songs where (usually inappropriately) appropriate or as corporate tie-ins (Cameron Crowe films being a very notable exception to this model). DH2 follows this trend to a T, giving us only tense strings for the action sequences, melancholic symphonies for the tragic, ominous minor-key dirges for the villains, and some Christmas tunes to remind us of the time of year. The films of the 90’s, however, again influenced by Scorsese’s expert use of pop and rock songs, mined a very different shaft (endnote 20) . One need look no further than Reservoir Dogs, and in particular the infamous ear scene, to see the point at which the fuse was lit on the bomb of post-modern application of music in 90’s film.

DH3 gives us a few pop/rock songs, notably during the credit sequence, though its most obvious application of ironic music comes when the villains invade the banks. A facetious, playful military march lilts from the screen as Irons and co. go about shooting bank employees and robbing billions of dollars in gold. Of course, as with any true studio film, the irony works against itself, as later in the film, the music is employed during a proper military scene in complete seriousness, therefore subverting its initial subversiveness.

Tarantino’s influence can be most obviously seen by contrasting the violence of the two films. Make no mistake: both are very violent. DH2’s violence is hoo-rah macho and near ridiculous. You can damn near see the packets of fake blood exploding when characters are shot. Throat slittings (they happen, and the camera does not move, and it’s a Oh hell no! moment) are grotesque, but are very obviously the work of make up artists. In the film’s concluding moments (which, in classic action film form, last for over fifteen minutes), a character takes an icicle through the eye. The after shot of the body and icicle is so painfully fake it’s more laughable than repellent.

DH3’s violence, on the other hand, is much more real. Very much under the influence of Reservoir Dogs and Pulp Fiction (which, let’s note, also starred both Jackson and Willis, and commercial success of which probably went great lengths to getting DH3 green lit), characters are caked in blood, sliced up, shoot to shit , and otherwise brutalized. The scene in which this is most evidenced comes toward the end of the film. Jackson and Willis are handcuffed to one another, back to back, on the top of a very big bomb. The camera pans and swoops around them, a continuous take, as they rap like Jules and Vincent in Pulp Fiction. The scene also evokes Reservoir Dogs, and the cop tied to the chair. Both characters are soaked with their own blood and covered in very realistic wounds. The film’s coup d’etat comes when Willis uses his teeth to pull a six-inch sliver of metal from a gash on his arm. The metal comes straight from a gash, very realistically, with a little spurt of blood following it out. It’s disgusting and cringe-worthy and all things post-Tarantino.

Echoes of Tarantino can been seen elsewhere, most obviously in the black/white buddy set up. Elsewhere, there is a scene of McClain beating a character near to death with a huge chain talking about the Adams Family that is pure Tarantino, and a bomb expert whose nerdy enthusiasm for bombs and their inner workings reminds us very much of QT himself, and his overwhelming enthusiasm for the minutia of film trivia.

All of these formal differences echo their times as resoundingly as the radically divorced handling of social and cultural issues. DH2 comes from the era of duality, in which competing monolithic states vied for control of the world. The formal techniques of DH2 echo the Cold War era’s sense of bombast, gianormity, and Wagnerian gravity. The clarity of the film stock, the static nature of the camera work, the traditional film score; all of it inline with a philosophy of good v. bad on an epic scale.

DH3, on the other hand, comes from the plurality, and as such is born of a world with endlessly more possibility. The focus post-Berlin Wall became on the small; the individual’s course through anincoherent, patchwork world, or, the smaller, developing nation’s search for cultural identity and a cohesive societal model. Thus the filmmaking is on a personal level. The director employs techniques that put the viewer into the action, attempting to dismantle the fourth wall, rather than positing the audience’s relationship with the film as it is, one of spectator and event.

Conclusion

So where does all of this leave us? Soviet duality v. post-Soviet plurality. Upstanding heroes who incite action v. drunken anti-heroes who are very grudgingly inserted into the action. A misrepresented racial view of the United States v. a well-intentioned, unfortunately racist attempt to deal with the multiracial tensions of the United States. Fat v. not fat people. The list goes on. What can we draw from all of this? Ultimately, this is nothing more or less than an exercise in extrapolating larger cultural implications from our pop art. In contrasting the presentation of characters, development of plot, formal techniques, and social and cultural depictions of the United States in Die Harder (DH2 – What a fuckin title!) and Die Hard with a Vengeance, we can plainly see the evolution of filmic, and, more broadly, cultural trends from the 1980’s of Reagan, Bush, the Soviets, and brute force to the 1990’s of Clinton, the developing world, and the dominance of intellectual trickery.

(A) A Soviet-era map (B) A more contemporary view of Europe

Endnotes

1. A quick note on the definition of 80’s v. 90’s: essentially what we mean by this is pre v. post Tarantino, the explosion of grunge v. hair metal, etc. More on this later.

2. Spike Lee reference not unintentional, but we’ll come back to that.

3. Two of whom are instantly recognizable as Terminator 2’s T1000 and the African baddie from Casino Royale, who’s actually a fantastic actor and has starred in such films as the stellar The Diving Bell and the Butterfly and the questionable The Limits of Control (which is typically lamentable Jim Jarmusch fare)

4. Though honestly it would’ve been a much more interesting 80’s theme. "Well, it seems as though the Predator is behaving as he is because his similarly dreadlocked, invisible alien parents didn’t love him. He developed, as an approval-seeking behavior, the habit of triangulating mercenaries in Central America’s jungles and severely fucking them up. His resentment of authority, resultant of strained parent-child relations, is particularly evident in his slayings of the governors of both California and Minnesota."

5. A film which went on to define an entire noir/horror crossbreed genre in the 90’s, with an evil criminal mastermind who plays games with his victims and commits decidedly violent crimes. See: The Bone Collector, Suspect Zero, and most especially the Saw films (which are by and large horrible but go great lengths to showing to popularity of this trend. Indeed, from Saw II forward, the villain is the only character of any importance. The “heroes” are a disposable series of torture victims).

6. The film makes a few small references about the Middle East – Jeremy Irons’ character is rumored to be in league with Iranians, and makes a quick comment about the Middle Eastern people he is working for. Interestingly, the Middle Eastern people he is working for have hired him to besiege downtown Manhattan. The film also contains a few shots of the World Trade Center towers, and a reference to the original Trade Center bombing. Watching the film post 9/11, with all of these things going on, is very creepy.

7. All of this very 90’s and psychoanalytical itself.

8. Authors will go on record here stating that DFW was in fact a very humble type of genius, and that he wasn’t following the know-it-all trend as much as becoming incredibly popular by hitting the zeitgeist with is intellectual rigor, all of his readers being snobby post baby boomers who prided their personal libraries and immaculate taste in fine cheeses. Like, really, with all these fucking footnotes, how could we speak ill of Wallace?

Also note that authors came of age during the 90’s and are very much sort of fancy intellectual writers enamored with verbal virtuosity and presenting themselves as clever – ah, how trends infiltrate the minds of the youth. Of course, all of this desperate need for intellectual validation probably comes from feelings of inadequacy, which brings us back to the psychoanalysis.

9. Which dialogue includes the character telling his nephews the need to go to school, to get educated, to stay away from the criminals and off the streets, to avoid eating the shit shoveled by the white people in the future, dialogue being so painfully stereotypical it’s a wonder Mr. Jackson brings so much dignity to his character.

10. Really? Black guys with a basketball? Again? Seriously…

11. And let’s talk a few things here. The scene takes place at 9am. Let’s give the filmmakers the benefit of the doubt and assume that this group of guys really is a degenerate clumping of drug dealers and gang bangers. Why are they awake at 9am? If they’re actually drunks, why do they have a basketball? Have you ever seen a crack head or alcoholic bright eyed and bushy tailed on the stoop at 9am, ready to give some lane? If anyone’s hanging out on the stoop at 9am its college students without morning classes or guys who work the night shift, and from my own Harlem and Brooklyn experience, these aren’t the guys who chug beer and stab people before noon (or at all, for that matter).

12. I must have missed the Nazi punks of the 90’s…

13. The first Diehard film has two lead, sympathetic African Americans, though the first film is also very progressive, intelligent, and subversive (as action films go), which is why we left it out of this discussion.

14. Interestingly, this is the only point in any Diehard film at which John McClain is overtly referred to as Irish. The third film seems interested, at least in a very small way, in acknowledging McCain’s Irish decent, and the important role that the Irish have played in New York City and especially it’s police history. By fleshing out the character as such, the filmmaker’s have yet again served to highlight American’s cultural and racial diversity.

15. The first two films, on the other hand, seem to want McClain as only the all-American hero, a man with only one nation and one cultural identity: American.

16. This would of course revert during Bush 2’s tenure, when a mass-Christian movement helped Mel Gibson’s “The Explicit Torture of Christ at the Hands of Satanic Jews” make hundreds of millions of dollars.

17. To go back even further, what we see in the 90’s is a reinvigoration of the French New Wave beliefs that film should be a personal, individual, sometimes whimsical, work of artistic expression.

18. Actually, a good deal of these guys – like Jarmusch, Van Sant, etc, rose out of the 80’s underground, much like groups such as Pixies and Dinosaur Jr., who essentially created the blueprint for 90’s rock music. Thus, though the 70’s largely informed the 90’s, it was the underground stalwarts of the 80’s who made much of it possible.

19. This directly parallels the difference between 80’s and 90’s cinema, business-wise. The 80’s films were produced by a very large, very industrial system as product. The indie films of the 90’s, which gave rise to the decade’s very different aesthetics, were independently financed, and the product of a small handful of people’s imaginations.

20. Not to shirk American mainstream experimental formalism, Frank Capra was a top-rate tracking shot guru. We need look no further than It Happened One Night, where, with a long track of Gable and Claudette Colbert, we experience the entirety of the Great Depression.

21. No reference to the brother from another mother who stuck it to Africa intended

Check out the trailers for the films below:

2 comments:

hi Will, I am writing from Culture Unplugged Studios - a new media studio focused on enabling networks of socially/spiritually conscious content and its creators. We are dedicated to bring authentic voices of diverse cultures to global audiences.Through this platform we intend to raise awareness of our audience - film-makers, film-lovers and conscious/global citizens and for which I will like to inquire if you can contribute to the blog on this platform. We hope to hear from you and begin a dialogue for collaboration, not only for writing/blogging but for effecting creative consciousness.

Regards,

nilankur

Did you know that that you can earn cash by locking selected pages of your blog or website?

To start just open an account with AdscendMedia and embed their content locking widget.

Post a Comment